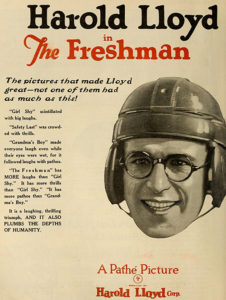

Retroformat Silent Films is presenting two screenings of THE FRESHMAN at the Hollywood Legion Theater Drive-In at Post 43 on Nov 28 (Sat) at 5:30pm and 8:15pm!

Retroformat Silent Films is presenting two screenings of THE FRESHMAN at the Hollywood Legion Theater Drive-In at Post 43 on Nov 28 (Sat) at 5:30pm and 8:15pm!

AFI Movie Club is presenting SAFETY LAST! today, with a wonderful introduction by actor and filmmaker Paul Feig. A big thank you to AFI and Paul for featuring Harold!

Watch Paul’s introduction to the film here: https://youtu.be/JwBoTCft9lk

And check out AFI Movie Club here! https://www.afi.com/movieclub/

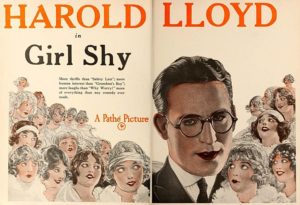

The East Texas Pipe Organ Festival will be playing GIRL SHY tomorrow (Wed 11/11) at 8pm CST. The virtual event is an “encore presentation” featuring organist Clark Wilson on the 1949 Aeolian-Skinner at First Presbyterian Church, Kilgore, Texas during the 2017 festival. Click here for tickets!

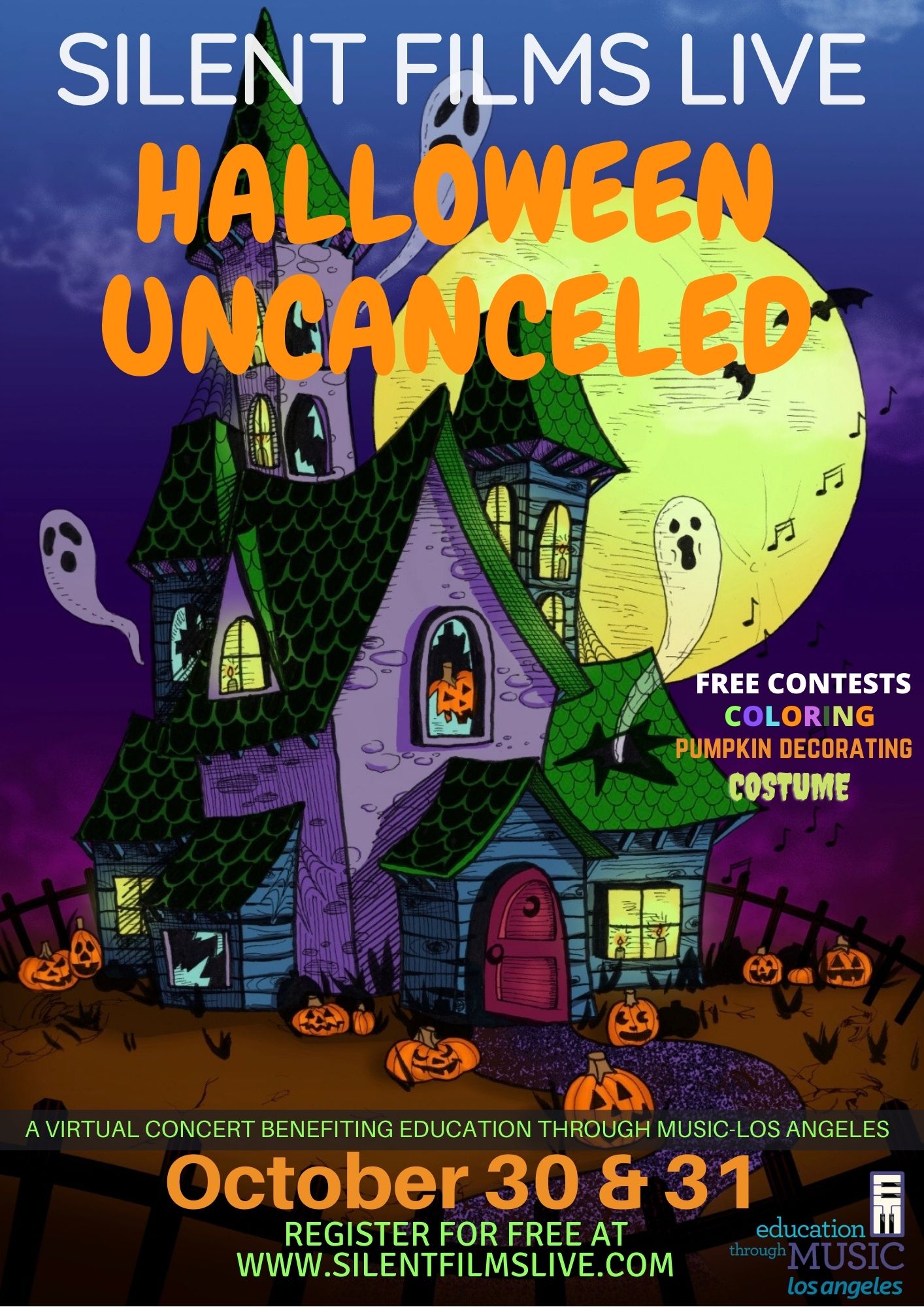

Check out Silent Films Live: Halloween UNcanceled this weekend!

Silent Films Live is a virtual show featuring new scores by elite Hollywood composers paired with selections from iconic silent films and performed by a chamber orchestra. Featured silent films include: Der Golem, Nosferatu, One Week, Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde, Phantom of the Opera, and A Trip to the Moon.

A Safety Last! clock is also featured (an homage to silent film star Harold Lloyd dangling from a huge clock, much the same way Christopher Lloyd’s Doc (no relation to Harold, but still a fun coincidence) does at the end of the film. “We knew we had to feature that,” Gale says.

But what about the Broncos clock? Well, that one has no hidden meaning — unless viewers want it to have one.

Gale explains: “It was just something the set dressers or props people found, it was interesting so we put it in the movie. Is Doc a football fan or a Broncos fan? We know he’s a baseball fan, so he could be a football fan. Or maybe he acquired it on a trip to Denver. We know he’s not from Denver, but maybe his mother was (his father, remember, was German and originally Von Braun). Clearly, we can invent many backstories out of a single prop, so in honor of BTTF day, I encourage readers to submit their own reasons why Doc would have this clock!”

By Ryan Parker / Source: The Hollywood Reporter