by Annette D’Agostino Lloyd

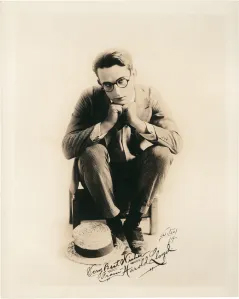

In April of 1919, Harold Lloyd signed an important new contract with Pathe distributors, calling for a new series of two-reel comedies. These two-reel comedies solidified Lloyd’s place among the finest comics of the day. As such, an increased advertising blitz was arranged, which called for new photographs and new portraits.

One Sunday afternoon, August 24, 1919, Harold Lloyd arrived at Witzel Photography Studio, in Los Angeles, to pose for a series of stills which would be used in ads for magazines, and posters.

One Sunday afternoon, August 24, 1919, Harold Lloyd arrived at Witzel Photography Studio, in Los Angeles, to pose for a series of stills which would be used in ads for magazines, and posters.

Earlier that month, Pathe had been testing some potent bombs for a thrill sequence in a non-Lloyd film. The bombs were tested in a park, and when one proved too potent (shattering a heavy oak table), it was determined that they would be too dangerous for on-screen use, and were discarded.

At Witzel’s, along with Lloyd and some of his gagmen, was a box of props, to be used in some of the shots. Among these props were some papier mache bombs, very similar in appearance to the potent real bombs tested by Pathe earlier in the month. Somehow (and a definitive explanation has never been arrived at), one real bomb got mixed in with the fakes — most likely due to their close resemblance. One of the poses called for Lloyd, then 26, to light a cigarette from one of these phoney bombs, in a pose which was to characterize his on-screen persona: devil-may-care, never intimidated by the obstacles that life presented to him. In a twist of fate, the only real bomb in the batch was the one handed to him.

Who handed the bomb to Lloyd is, indeed, as newsworthy as the event to come — Frank Terry, also known as Nat Clifford, who was one of Lloyd’s valued gagmen. Terry, whose life reads like the scenario to a great intrigue picture (beyond bigamous marriages and fugitive exploits, he had several bouts with alcohol and was jailed for a time), was a writer and actor, most notably with the Hal Roach Studios. He can be seen in numerous Laurel & Hardy films (among them Me and My Pal and Fra Diavolo), and was in Lloyd’s High and Dizzy (1920).

Once handed the bomb, Lloyd placed the already-lit cigarette to the wick of the thought-fake bomb. The excessive smoke, strange for a papier-mache, made Lloyd realize that the picture would suffer. He figured that they’d try again, with another bomb — as he reached to place the bomb on the table, it blew.

The force of the blast tore a hole in the sixteen-foot ceiling of the studio. Terry’s upper dental plate was cracked in half in his mouth. The photographer fainted. Lloyd, still in his mark, didn’t register what happened until moments later, when the pain just started to set in. He described his face as “raw meat.” He couldn’t see out of either eye after the blast. However, more painful was the permanent reminder of this fateful day: the thumb and forefinger of his right hand were severed.

Lloyd was rushed to the Methodist Hospital, which would be his home for the next 16 days. His eyesight eventually returned, but for a while the doctors feared for his right eye. Physicians also worried that gangrene might set in on his face, and the gashes in his lips produced cracks that were very painful. Lloyd noted that “the pain was considerable, but trivial compared with my mental state.” He had good reason to be worried.

At the time of the blast, Lloyd’s reputation as an up-and-comer in film comedy was solidified, and his most important work was in front of him. He felt certain that his career was over, and sat in his bed frantically figuring what he was going to be able to do now: 26 years old, and, supposedly, out of work. He had, though, a basic optimism that transcended his character’s enthusiasm, and he realized that he did have a future in producing, or writing, or directing, either in film or in theatre. He was not about to give up — in that way he and his on-screen persona were most similar.

Lloyd received hundreds of get well wishes, from the cream of the Hollywood crop: the notes still survive, in the California vault that houses Lloyd’s archives. Cards and notes from Roscoe Arbuckle, Stan Laurel, Bebe Daniels, and others, made Lloyd feel remembered and loved by his comrades. Among the cards and letters was a note from a Massachusetts fan, which read:

“I’ve had some awful illnesses

And accidents that stretched me flat.

But anyway I’m still alive,

And lots of people can’t say that.”

With sentiments like that, how could he not recover?

Hal Roach and Sam Goldwyn (who started out life as Sam Goldfish, glove salesman), teamed to inspire a revolutionary prosthetic device, which might hold the key to Harold’s returning to the screen. The prosthesis, still pretty remarkable by today’s standards, called for a rubber mold to be taken of Lloyd’s left hand. The mold was reversed to simulate the incomplete right hand. The area that was missing was cut, and fitted into a thin leather glove, and when Lloyd’s right hand was inserted into the glove, it looked complete. The index and middle fingers of the glove were stitched together, meaning that movement of the flexible rubber index finger was possible, whenever the middle finger moved. The thumb remained immobile, and logically so. The leather glove was held on, tightly, by a rubber band garter system, which fastened to Lloyd’s upper arm. When covered in makeup, the prosthesis was hard to detect, which was exactly the way Lloyd wanted it…

Harold was a natural righty — the loss of two fingers from that hand necessitated an increased mobility with his left hand. He gained that, and became essentially ambidextrous, through intensive handball training. Always a fan of the sport, he increased his practice, and this timing and focus, so necessary to that game, made it such that he could do anything with his left hand now, even sign his autograph — and, this he did, on-screen, many times.

Harold Lloyd NEVER publicly talked about the loss of the fingers on that fateful August afternoon. Sure, he talked about the accident, plenty of times, often calling himself “a most fortunate unfortunate.” However, a letter, written by Harold to Pathe during his recuperation, seems to be the only public acknowledgment of the loss of his fingers. But, the fingers were not an issue, and he never mentioned it, even in his 1928 autobiography, An American Comedy. The logic behind this, in Lloyd’s mind, was quite sound: he did not want his growing audiences to come to see his films out of pity, or sympathy, or curiosity. He desired an audience that purely desired good, clean laughter — and that’s what they got, always.

Which makes Harold Lloyd a pretty remarkable man, and a worthy role model. Consider, for a second, the potential at the box office — this accident, and his eventual recovery from it, could have been a financial bonanza, and could have resulted in tremendous publicity, as well as serving as a source of immense inspiration for his fans (“Gee, if Harold Lloyd can get along with only eight fingers, then I can get through…”). Lloyd, always a humble man, did not want such publicity, or such notoriety. He simply wanted to make audiences laugh, and provide inspiration through his on-screen character, not his off-screen self. He desired, always, to keep the character and the man separate — that is why, only two times after he shed the Lonesome Luke persona, did he take his glasses off on-screen (in Pinched [1917], and, with his back to the camera, in Professor Beware [1938]).

So, the next time you see a post-accident film (and, remember that he was in the midst of filming Haunted Spooks at the time of the blast), and are marvelled at the athletic prowess and enthusiastic movements of Harold Lloyd, think about the fact that these on-screen feats are being accomplished with one and a half hands. He climbed the building in Safety Last, hung from the double-decker bus in For Heaven’s Sake, and even sat in a taxi in his underwear in Professor Beware. (The latter scene, in which he wore a sleeveless undershirt, is amazing, and is thanks to the makeup genius of Wally Westmore, who always was a dear friend to Harold.)

This was a man who could have milked his disability for all it was worth, but didn’t — because his character meant more to him than his misfortune, and because his audiences meant even more than that. Quite a man…

…An entire chapter devoted to the accident can be found in Harold Lloyd: Magic in a Pair of Horn-Rimmed Glasses, as August 24, 1919 is, arguably, the most crucial turning point in the life and career of Harold Lloyd.